Anticoagulation Dosing Calculator

This tool helps determine appropriate anticoagulant therapy based on kidney function and liver disease severity.

Enter your patient's eGFR and liver disease severity to see anticoagulation recommendations.

Why Anticoagulation Gets So Complicated in Kidney and Liver Disease

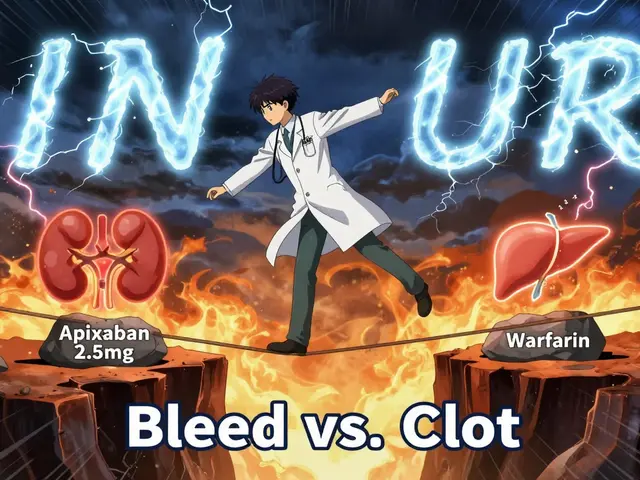

When your kidneys or liver aren’t working right, taking a blood thinner isn’t like popping a regular pill. It’s like walking a tightrope - one wrong step and you could bleed too much, or clot too hard. This isn’t theoretical. In the U.S., over 37 million people have chronic kidney disease, and nearly 6 million have chronic liver disease. Many of them also have atrial fibrillation, which means they need anticoagulation to prevent strokes. But most of the big studies on blood thinners like apixaban or rivaroxaban left these patients out. So doctors are left guessing.

How Kidney Disease Changes the Rules for Blood Thinners

Your kidneys clear most of the drugs you take. When they fail, those drugs build up. That’s why dose adjustments aren’t optional - they’re life-or-death. For early-stage kidney disease (eGFR ≥45), DOACs like apixaban and rivaroxaban are generally safe at standard doses. But once eGFR drops below 30, things get messy.

Apixaban is the only DOAC that still has some wiggle room here. The FDA allows 2.5 mg twice daily for patients with eGFR under 30, based on data from the ARISTOTLE trial showing it cut major bleeding by 70% compared to warfarin in this group. Rivaroxaban and dabigatran? Contraindicated. Edoxaban? Only if you drop the dose to 30 mg daily - and even then, it’s a gamble.

For patients on dialysis, the data is even thinner. Some hospitals use apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily. Others avoid DOACs entirely. Why? Because studies show dialysis patients on DOACs have trough levels around half of what’s seen in healthy people. But does that mean they’re underdosed? Or just safer? No one knows for sure. One 2021 study of over 12,000 dialysis patients found DOACs led to fewer bleeds than warfarin - but stroke rates were the same. That’s the paradox: you can reduce bleeding without increasing stroke risk, but you can’t prove you’re preventing strokes either.

Liver Disease: It’s Not Just About INR

Doctors used to think the INR was the boss when it came to liver disease. If your INR was 2.5, you were anticoagulated. But in cirrhosis, that number lies. The liver doesn’t just make clotting factors - it makes anticoagulants too. So when the INR is high, it doesn’t mean you’re more likely to bleed. It just means your liver is failing.

That’s why Child-Pugh scoring matters more than INR. Child-Pugh A? You can usually start a DOAC at full dose. Child-Pugh B? Proceed with caution. Child-Pugh C? Don’t even think about DOACs. The RE-CIRRHOSIS study showed these patients had more than five times the risk of major bleeding on anticoagulants.

And then there’s platelets. About 76% of cirrhotic patients have low platelet counts. A count under 150,000 is common. Under 50,000? That’s a red flag. Some hepatologists won’t even start anticoagulation if platelets are below that. Others use TEG or ROTEM - tests that show how blood actually clots in real time. But only 38% of U.S. hospitals have them. So most doctors are still flying blind.

Warfarin vs. DOACs: The Real Trade-Offs

Warfarin isn’t dead. In fact, in advanced liver or kidney disease, it’s often the only option left. Why? Because we know how to reverse it. Vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, prothrombin complex concentrate - they’re all available, even in small hospitals. And if you’re on dialysis and have a mechanical heart valve? Warfarin is still the standard. DOACs aren’t approved for that.

But here’s the catch: warfarin is unpredictable in liver disease. One study found only 45% of cirrhotic patients stay in the therapeutic range more than 60% of the time. That’s compared to 65% in people with healthy livers. And the variation in INR? It’s 42% - almost double what it is in normal patients. So you’re checking INR every week, adjusting doses, and still not knowing if you’re safe.

DOACs? They’re more consistent. No need for frequent blood tests. But reversal is harder. Andexanet alfa reverses apixaban and rivaroxaban - but it costs $19,000 per dose and only 45% of U.S. hospitals carry it. Idarucizumab reverses dabigatran, but it’s useless for the others. And dabigatran? You can’t even use it if your kidneys are bad.

Apixaban wins on safety. In patients with eGFR 25-30, it cut major bleeding by 31% compared to warfarin. It also reduced intracranial hemorrhage by 62%. But in dialysis? The data is observational. No randomized trials. So while some doctors swear by apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily, others have seen patients bleed out after starting it. One Reddit thread from a nephrologist described a patient who had a retroperitoneal hemorrhage - dead within hours. Another said he’s treated 15 dialysis patients on apixaban for two years with zero bleeds.

What Do the Experts Actually Recommend?

There’s no global consensus. The European Heart Rhythm Association says don’t use DOACs in dialysis patients. The American College of Chest Physicians says apixaban might be okay. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases says avoid DOACs in Child-Pugh C. But they all agree: treat the patient, not the lab numbers.

Dr. Daniel Wojdyla, who worked on the ARISTOTLE trial, says the lack of evidence doesn’t mean DOACs don’t work - it just means we haven’t studied them enough. Dr. Mark Crowther warns that assuming pharmacokinetics equal clinical outcomes is dangerous. One study found rivaroxaban doubled gastrointestinal bleeding risk in dialysis patients compared to warfarin.

And then there’s the nuance. Portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis? That’s a different game. You’re not trying to prevent a stroke - you’re trying to stop a clot from killing the liver. Some experts say you need stronger anticoagulation here, even if the patient is Child-Pugh B. Others say the bleeding risk is too high. There’s no algorithm. Just judgment.

How to Actually Manage This in Real Life

If you’re managing a patient with both kidney and liver disease, here’s what works:

- Check eGFR with CKD-EPI, not just creatinine. Creatinine alone is wrong in advanced disease. Use the formula.

- Use Child-Pugh score, not INR. If the patient is Child-Pugh C, avoid DOACs. Period.

- Monitor platelets monthly. If they drop below 50,000, reconsider anticoagulation.

- For dialysis patients, consider apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily. It’s the only DOAC with any real-world support. Avoid rivaroxaban and dabigatran.

- For cirrhosis with AF, stick with warfarin if you can’t monitor closely. But if you have access to TEG/ROTEM and a specialist team, DOACs might be safer.

- Reversal planning is non-negotiable. Know what’s available at your hospital. If you can’t reverse the drug quickly, don’t start it.

- Coordinate care. Nephrologists and hepatologists need to talk to cardiologists. Most hospitals don’t have protocols for this. You might have to build them yourself.

One clinic in Portland started a joint clinic for liver and kidney patients on anticoagulants. They meet monthly. They track every INR, every platelet count, every bleed. In a year, they cut their major bleeding rate by 40%. That’s not magic. That’s teamwork.

What’s Coming Next

Two big trials are underway. The MYD88 trial is randomizing 500 dialysis patients to apixaban vs. warfarin - results expected in 2025. The LIVER-DOAC registry is tracking 1,200 cirrhotic patients on DOACs worldwide. The FDA is also considering new labeling for apixaban in end-stage kidney disease based on modeling data.

KDIGO is updating its guidelines in late 2024. That could change everything. Until then, we’re operating in the gray zone. The best thing you can do is document your reasoning. If you choose apixaban in a dialysis patient, write why. If you hold anticoagulation in a Child-Pugh B patient with portal vein thrombosis, explain your thinking. Because when something goes wrong, the court won’t care about the guidelines - they’ll care about your notes.

Bottom Line

There’s no perfect answer. But there are better choices. Apixaban is the safest DOAC in kidney disease. Warfarin is the most reversible in liver disease. Avoid dabigatran in kidney disease. Avoid all DOACs in Child-Pugh C. Monitor closely. Talk to specialists. And never, ever assume the lab numbers tell the whole story. The patient - not the numbers - is what matters.